By Cassandra Stubbs, Director, Capital Punishment Project

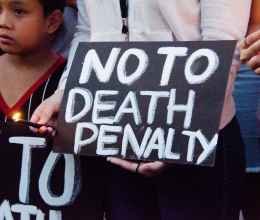

America made big strides in 2019 on its path to dismantle the racist, unfair, and inhumane death penalty. Today, dramatically fewer states permit the death penalty than any time in the modern era, and the number of people on death row is at a 27-year low.

Bi-partisan supermajorities in the New Hampshire legislature abolished the death penalty in May, making it the 21st state to formally reject the punishment. Governor Gavin Newsom imposed a sweeping moratorium on executions in California, closing the death chamber in the state with the largest death row in the country and prohibiting the execution of 737 death row prisoners. Four states — California, Oregon, Colorado, and Pennsylvania — are now under official Governor-imposed moratoria, bringing the total number of states that wouldn’t carry out an execution to 25. Ten years ago, just 12 states prohibited executions. In other words, the number of states prohibiting executions has more than doubled in the last decade — a remarkable pace of change.

The shift in states rejecting the death penalty is mirrored by the movement in public opinion away from capital punishment. The Gallup Poll has tracked public opinion about the death penalty versus life imprisonment since 1985. This year, for the first time since Gallup began tracking public opinion on this issue, a majority of Americans (60 percent) prefer life imprisonment to the death penalty.

Part of this shift is the clear proof that the government does not always get it right — innocent people have been sentenced to death, including the 166 people who have been formally exonerated. This year brought even more proof that the death penalty cannot shake its innocence problem. In 2019, two men, Charles Ray Finch and Clifford Willians Jr., both of whom were convicted and sentenced to death in 1976, were exonerated and released. Additionally, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted an indefinite stay to Rodney Reed after a groundswell of public opposition clamored against his execution in light of powerful new evidence of his innocence. Other names like James Dailey, Richard Glossip, and Larry Swearingen also made headlines for credible innocence claims. For Swearingen, those news stories came too late.

While a year of much progress, 2019 was also a year plagued by shameful state executions and the reckless attempt by the federal government to rush the executions of five men after a nearly two decade de facto moratorium. The Supreme Court allowed Alabama to execute Dominque Ray, a Black Muslim who was denied access to the spiritual advice of his Imam — a comfort guaranteed to Christian prisoners. Just weeks later, the Court stopped the execution of Patrick Murphy, a white Buddhist man, triggering concerns that race and religion played a role in the disparate outcomes.

Other unconscionable executions from 2019 include: Georgia’s execution of Ray Cromartie without permitting a simple DNA test that could have fully exonerated him; Missouri’s execution of terminally ill Russell Bucklew in the face of evidence that his execution was likely to be torturous; and Tennessee’s execution of legally blind Lee Hall, Jr. The Supreme Court and the government of South Dakota alike failed Charles Rhines, allowing his execution despite evidence that his jurors sentenced him to death because of their anti-LGBT prejudice.

This year was mixed in terms of the courts willingness to grapple with intractable problems of racial discrimination in the death penalty. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear cases from Oklahoma that challenged the systemic racial bias in the imposition of the death penalty, as well as from California, where the state supreme court had upheld the outrageous claim that a prosecutor’s decision to exclude jurors who did not oppose the OJ Simpson verdict was unrelated to race.

But the North Carolina Supreme Court granted review in six cases where the petitioners were yanked from death row, to life without parole, and back again — without due process or new trials — after they had proved racism infected their cases and the state legislature repealed its anti-discrimination law. And the U.S. Supreme Court issued a powerful decision in Flowers v. Mississippi, reaffirming its commitment to overturning cases in which prosecutors secured death sentences by systematically excluding qualified Black jurors from jury service.

The modern death penalty has churned along for over 40 years since the Supreme Court permitted its reinstatement in Gregg v. Georgia, after finding it unconstitutionally biased and arbitrary in 1972. After more than 40 years, none of the major problems with the death penalty have been addressed. An outgrowth of lynching and slavery, the modern death penalty is still racially biased. Supposed to be reserved for the “worst of the worst” defendants, the death penalty is handed down more often for those with the worst lawyers — not the worst crimes. Geography, money, and race are still the best predictors of who will receive the death penalty. The good news from 2019 is that the country is accelerating in its efforts to finally break with the inhumane and unjust punishment.

Part of an end of year wrap-up series. Read more:

In the Midst of Trump’s Attacks, Offshoots of Progress in Congress for Immigrants’ Rights

2019 was a Watershed Year in the Movement to Stop Solitary Confinement

The 2020 Election Promises Record Turnout

The Battle for Abortion Access Is In the States

In 2019, We Fought Across the Country to Dismantle Mass Incarceration. We Won on Multiple Fronts.

Under Attack by Trump, Immigrant Justice is Advancing in the States