By Dylan Hayre, ACLU Justice Division Campaign Strategist

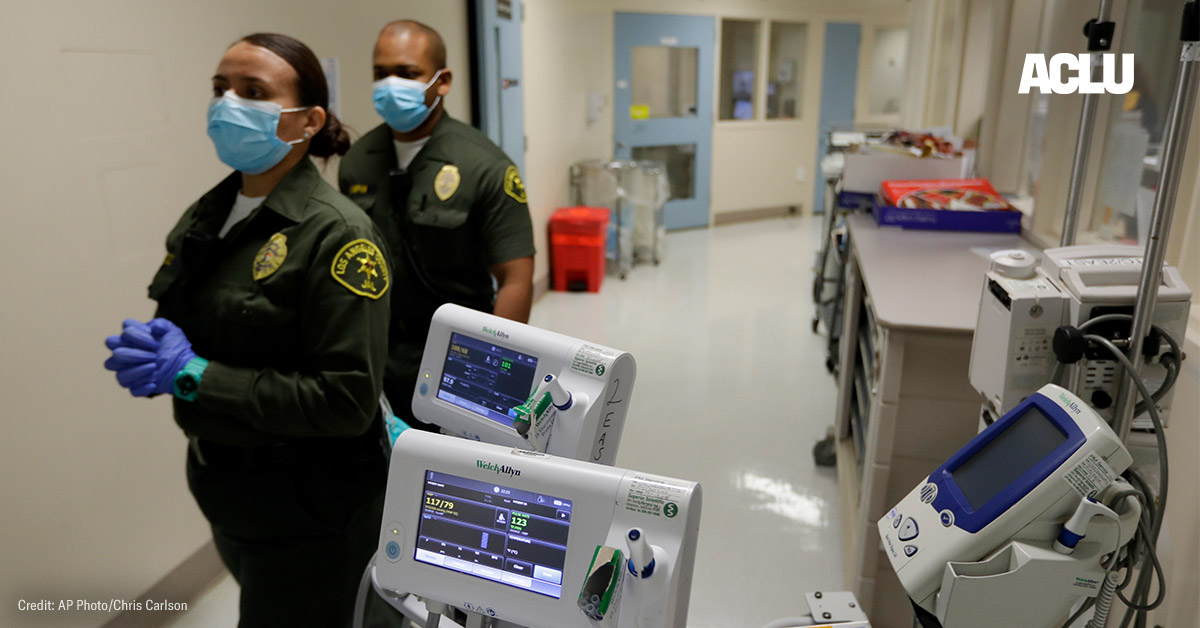

Since the inception of this pandemic, it has been clear that incarcerated people are particularly at risk from COVID-19. In addition to the clear, consistent guidance from public health experts, incarcerated families, corrections staff, and data scientists urged states to take action to prevent tragedy.

Unfortunately, states failed to heed these warnings and have failed to protect incarcerated people, facility staff, and communities at large from the looming threat of COVID-19.

This is the core finding of a new ACLU report: “Failing Grades: States’ Responses to COVID-19 in Jails & Prisons,” co-authored with Prison Policy Initiative. The report evaluated states based on four criteria:

- Testing all staff and incarcerated people, and making sure everyone had access to personal protective equipment;

- Whether the governor issued an executive order to stop the churn of people coming into jails, and to immediately get people out of jails and prisons;

- Sharing data, disaggregated by race, so the public has insight into how the crisis is unfolding and being addressed; and

- Actually reducing the number of people in jails and prisons — the most important step any state can take in this moment.

There is no doubt that the responsibility to respond to this crisis falls heavily on states: Of the 2.3 million people incarcerated in this country, over 1.9 million people are in state prisons or local jails. These facilities are cramped, unhygienic, and designed to inhibit a person’s ability to protect themselves. Social distancing is impossible. Human contact is unavoidable. Soap and medical attention are prohibitively expensive, while hand sanitizer is often regarded as contraband. And unfettered access to open air and outdoor spaces is essentially nonexistent.

The results of states’ failure to respond are therefore as tragic as they were predictable. Jails and prisons have become the epicenter of this pandemic. Most of the largest COVID-19 clusters are in jails and prisons, and the largest hotspot in most states is inside a jail or prison. Moreover, to date, over 600 incarcerated people and over 50 staff have died. These numbers will only increase as COVID-19 continues to run rampant in these facilities.

This impacts all of us. Not forcefully confronting COVID-19 in jails and prisons will have deep reverberations in neighboring communities. Just as importantly, this travesty exacerbates the racial inequities that define mass incarceration. We know that the egregious harm created by our carceral systems has always been deliberately concentrated in Black and Brown communities. A similar disparity has played out in the COVID-19 pandemic — a product of generational underinvestment in the housing, health care, and other resources that communities depend on for protection in moments like this.

Yet it is not too late to change course. It is not too late for leadership. This report offers more than an evaluation of what has not happened; it also offers some ideas and a blueprint for what must happen now. The lives lost cannot be brought back, but other lives can still be saved. People can still be allowed to go home. Corrections staff can work without fear of carrying a virus back to their families. And we can actually combat this pandemic while caring for and centering people’s humanity and dignity.